Nathan Chrismas is an Aspirant AC Member and lichenologist. He studies the diversity and function of lichens in polar and alpine environments. His latest project, CryptFunc, involves understanding the functional ecology of Arctic-alpine lichens in the Cairngorms. Here he explains more about these remarkable organisms and how their distribution is being impacted by environmental pressures.

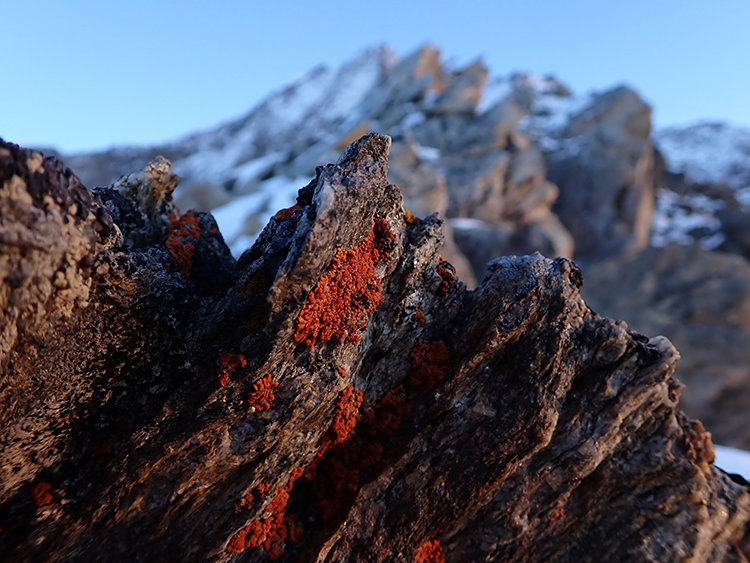

The elegant sunburst lichen (Rusavskia elegans) on the south-east ridge of the Weissmies (AC Aspirants Meet, 2023) - Nathan Chrismas

Mountains can be inhospitable places. Biting winds, long cold nights, exposure to the sun, and lack of food are all familiar experiences to alpine climbers. Mountaineers tend to be hardy folk though and are happier than most to tough it out when conditions turn grim. But even the most resilient among us don’t come close to another group of mountain enthusiasts: the lichens.

Lichens are a paradox. They are incredibly abundant, having found ways of colonising almost every terrestrial habitat on the planet. By some estimates they are dominant organisms on as much as 8% of the Earth's surface. Yet to our eyes they are often invisible, obscured by their ubiquity. It is only when they are at their most flashy that lichens draw our attention - a bright orange splash on the tip of a boulder, a fluorescent yellow tangle on the trunk of a tree - but look closer and you will begin to see lichens everywhere you look. This is no more true than for climbers and explorers. The most exposed sea cliffs, the highest mountains, and wide expanses of Arctic tundra; all are home to a rich diversity of lichens growing on rocks, soil, moss, and plants.

Their biology is fundamental to their versatility. It’s almost impossible to find anything living in complete isolation, and lichens quite literally embody this principle. They are a fungus and algae living in close coordination with each other; the algae generating enough sugar through photosynthesis to nourish both themselves and the fungus, while the fungus provides a structure within which those algae can grow. It’s this symbiotic relationship that has allowed lichens to occupy such an incredibly diverse range of habitats. By ‘farming’ algae, the lichen fungus can survive in places nothing else can, including the polar regions and the high mountains. Interestingly, the word ‘symbiosis’ was first invented by Albert Bernhard Frank in 1877 to describe the relationship seen in lichens.

In the UK, mountainous lichen habitats are no more apparent than in the Cairngorms. These granite hills are a unique environment on our islands. Scotland’s latitude means that species associated with the high mountains in central Europe can survive here at much lower elevations. The relatively dry Cairngorm Plateau has characteristics reminiscent of Arctic tundra, the sort of landscape more readily associated with Finland or Svalbard. Just as reindeer roam the broad expanses of tundra in Finland, so the Cairngorm reindeer herd have made the plateau their home. When winter comes, both Scottish and Scandinavian populations turn to the only reliable source of food: reindeer lichens. These bushy species, like Cladonia arbuscular, cover huge areas of exposed and wind-clipped terrain, dominating in landscapes where flowering plants are at their limit.

The author examining lichen heath on Meall a’ Bhuachaille

The author examining lichen heath on Meall a’ Bhuachaille

Both the mountains and the polar regions are changing, and the lichens along with them. The highlands of Scotland already support relict populations of lichen species that were once widely distributed at the end of the last ice age, creeping further northwards and to higher elevation at a literally glacial pace as the ice retreated. Today, as our climate warms more rapidly than ever before, these shifts in the distribution of lichen populations are happening right before our eyes. The white worm lichen (Thamnolia vermicularis) is a true arctic-alpine specialist that can be found fairly frequently in the Cairngorms. However, last year it was declared extinct in North Wales, presumed lost to warming, grazing, and trampling. Many more lichen species are likely to suffer a similar fate.

Of course, lichens will always be there in the hills. Whatever the environmental conditions, there will almost always be lichens adapted to them. But the species we see are not as fixed in stone as they might appear and the arctic-alpine specialists are important ones to watch as our global climate changes.

White worm lichen (Thamnolia vermicularis) growing amongst a bushy reindeer lichen (Cladonia arbuscular) on the Cairngorm plateau - Nathan Chrismas

White worm lichen (Thamnolia vermicularis) growing amongst a bushy reindeer lichen (Cladonia arbuscular) on the Cairngorm plateau - Nathan Chrismas

Lichens are amongst the most under-studied groups of organisms on the planet and there are still many open questions about the fundamental principles that underlie their biology and ecology. They play an as yet poorly understood role in global nutrient cycles, introducing and recycling carbon and nitrogen in otherwise nutrient depleted environments. Our new research project based in the Cairngorms hopes to shed some light on these processes and explore what lichens at home can tell us about the fate of a future Arctic.

Other projects are focusing on the mechanisms behind the interactions between fungi and algae, probing the very nature of mutualistic interactions; it’s an exciting time to be involved in lichen research. All of this, while the questions of how many lichens are even out there remains unanswered. New species are still being described here in the UK and, with no baseline estimates of lichen biodiversity in many of the planet’s most remote regions, the race is now on to document as much as we can about these remarkable organisms as they respond to their rapidly changing habitats.

If this has piqued your interest, below are a few species to keep an eye out for the next time you’re in the Cairngorms, the Alps or anywhere cold or high. You can also find more information on the lichens of the Cairngorms in The Montane Heathland Lichen Guide by Andrea Britton.

Alpine bloodspot lichen (Ophioparma ventosa): This eye-catching Arctic-alpine grows on rocks and gets its name from its bright crimson fruiting bodies.

It has a fairly broad distribution and can be found as low down as Dartmoor.

Grey Witches hair (Alectoria nigricans): This dark lichen can be hard to spot and looks like a tuft of hair.

It grows near the ground in very wind-exposed environments like ridges.

Iceland lichen (Cetraria islandica): This is a ‘shadow lichen’ of alpine heath; hard to spot, but when you know what to look for you’ll start seeing it everywhere!

Map lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum) photographed on Skye’s Inaccessible Pinnacle (AC Highlands and Islands Meet, 2023)

Crinkled snow lichen (Flavocetraria nivalis): This pale yellow leafy lichen is a common sight on alpine heath, but in the UK is only found in the Cairngorms.

Crinkled snow lichen (Flavocetraria nivalis): This pale yellow leafy lichen is a common sight on alpine heath, but in the UK is only found in the Cairngorms.

Its colour works as a sunscreen to protect it from exposure to UV radiation.

You can follow Nathan Chrismas on Twitter, Threads, Facebook and Instagram.

You can also catch him in the new BMC series The Landscape Project which explores the natural history (including lichenology) of UK climbing venues.